by Wei Li

The United States has the highest number COVID-19 cases and deaths in the world, with over six million confirmed cases and over 189,000 total deaths in the country as of September 9, 2020. Within the US, the pandemic is impacting racial groups differently, disproportionately affecting Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. As the country is slowly reopening the economy and schools, it is important to keep these vulnerable populations in mind as we move forward.

COVID-19’s unequal impact

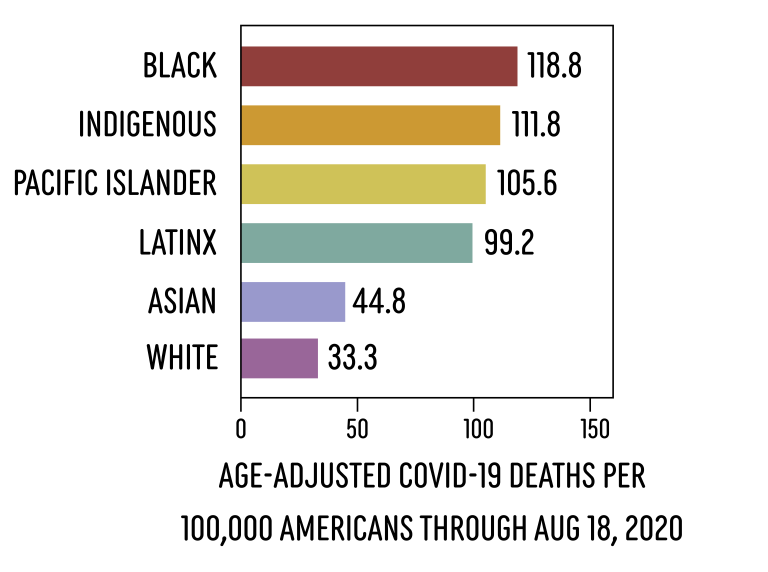

The CDC’s COVID-19 data tracker shows that the death rates due to COVID-19 are the highest among Black and Indigenous people, followed by Pacific Islanders and Latinx people. As of August 19, 2020, a separate non-profit organization, APM research lab, independently collected data from each state to validate the CDC’s results (Figure 1).

(Figure 1: COVID-19 is hitting certain communities harder than others. Data from CDC and APM research labs both show corroborating evidence that COVID-19 mortality rates are higher among BIPOC communities. These numbers are age-adjusted data from APM research lab.)

If you were to adjust the mortality data for these vulnerable populations such that they were instead dying at the rate at which White people are dying, you would find that roughly 19,500 Black, 8,400 Latinx, 600 Indigenous, and 70 Pacific Islander Americans would still be alive right now. Furthermore, many more younger BIPOC people are being hospitalized and dying of COVID-19 as compared to White populations, even though younger people have less risk of severe symptoms or mortality.

However, it is important to note that all of these numbers are estimates. The data is incomplete, as some states are not reporting the race and ethnicity of the cases in their data. Nonetheless, despite the incompleteness and inaccuracies in the data, the drastic disparities shown are enough to tell us that certain communities are indeed being hit by the virus harder than others.

Why is there a racial disparity?

It’s easy to jump to a conclusion that this racial disparity may be due to genetic factors, but there is currently no scientific basis for that (in fact, there is no scientific evidence that different races even have distinct genetic identities — you may be more genetically similar to someone of a different race than someone of the same race). So why is there such a huge racial disparity in reported COVID-19 cases?

Firstly, it is more difficult for BIPOC communities to remain safe during the pandemic. Since the virus mainly spreads from person to person, the best way to prevent contracting COVID-19 is appropriate social distancing. However, social distancing is a privilege that many people of color cannot afford because they make up the majority of essential workers and they are generally less able to work from home. Even if these workers could stay at home, they may be more likely to live in densely populated areas and reside in multigenerational and multifamily households, making it even harder to follow social distancing recommendations. Data has shown that BIPOC people are also more likely to depend on public transportation and live in areas with a lack of access to grocery stores, which makes it challenging to stock up on supplies for staying at home. Many communities, especially Indigenous territories such as the Navajo Nation, also lack access to clean water, which makes it difficult to practice proper hand-washing.

Furthermore, many inequalities that existed pre-pandemic have only worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, communities with majority Black and Latinx populations are more likely to have limited access to primary care physicians and other medical facilities, because private medical providers tend to steer away from neighborhoods that are less likely to own insurance and have less financial resources. A similar problem is revealed when it comes to COVID-19 testing. Testing sites in BIPOC communities are often found to be scarce and understaffed, because private medical providers are once again less willing to set up testing sites in these communities.

Let’s take a look at Texas: after a stay-at-home order on March 31, 2020, it was one of the first states to reopen on May 1, 2020. Initially reported on May 25, 2020, testing sites were disproportionately located in whiter neighborhoods in four out of six of the largest cities in Texas. More specifically, Dallas, one of the hardest hit cities in Texas, had the greatest disparity in the number of testing sites between the city’s predominantly white neighborhoods in North Dallas and the predominantly Black or Hispanic neighborhoods in South Dallas. In an attempt to solve this issue, Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson requested providers like Walgreens and CVS to open up more testing facilities in these underserved communities. The number of testing sites has been greatly increased since then, but there is still a noticeable difference in the number of testing sites between the north and south ends of the city today.

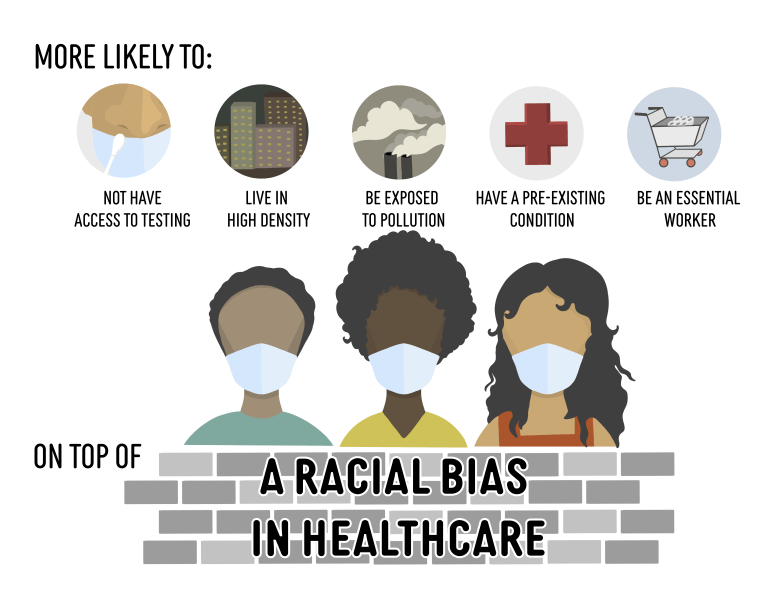

There are many more factors that contribute to the racial disparity in COVID-19 cases (Figure 2). The social inequalities described previously also result in increased presence of other health disparities in BIPOC communities like obesity and Type 2 Diabetes (even though there are genetic factors that will increase one’s risks of getting these diseases, there is no evidence showing that these genetic factors are increased in any race or ethnicity). These illnesses are comorbidities (co-occurring illnesses or conditions alongside a primary disease, in this case COVID-19) that are known to lead to an increased risk of severe symptoms and mortality from COVID-19. BIPOC neighborhoods in the US have also been shown to be more likely to be exposed to air pollution, which is yet another risk factor for development of severe cases of COVID-19. Additionally, evidence suggests that racial bias hinders the diagnosis and treatment of Black Americans. For example, back in April when testing was less readily available, Black Americans with COVID-19 symptoms were less likely to be given a COVID-19 test.

(Figure 2: Non-exhaustive list of factors contributing to racial disparities in COVID-19. Racial disparities, such as lack of access to healthcare providers in BIPOC communities, are not unique to COVID-19. These inequalities have always plagued BIPOC people, and COVID-19 is just another spotlight for them.)

All of these (non-exhaustive) factors, whether they stem from systemic inequalities or racism, have always existed in our society, and they are now exacerbating the racial disparity during these unprecedented times. The pandemic did not create these problems of inequality in healthcare – it has only shone a spotlight on them.

This disparity in COVID-19 outcomes is not unique to America. Outside the US, minority groups all over the globe are also found to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19, such as in the United Kingdom, Norway, Singapore, and Saudi Arabia. In the case of Singapore, a small island country in Southeast Asia, they were initially able to keep the number of COVID-19 cases consistently low throughout February and March when the virus first hit Asian countries. In their COVID-19 response efforts, however, they neglected their most marginalized population: millions of migrant workers living in poor housing conditions with poor access to healthcare. Within a month, the number of cases shot up from a little over 1,000 total cases at the start of April, to more than 17,000 cases by the end of April, with migrant workers making up 85% of the cases. The country has since flattened the curve through rigorous testing and providing additional housing for infected workers, but the health disparity still prevails. The COVID-19 crisis has indeed aggravated existing inequalities all over the world.

COVID-19: a microcosm of healthcare and its inequality

It is unsurprising that there is a racial disparity in COVID-19. After all, racial disparities in healthcare have always been prevalent throughout history. If we observe the countless pandemics in the past, such as the Black Death in the 1300s and the more recent 1918 flu pandemic (also known as the Spanish flu), they have shown that the most socially marginalized populations tend to suffer disproportionately.

Looking forward, what can we do to address this disparity? Currently, the state of Massachusetts assembled a health equity task force to study these health disparities. Hopefully, they will be able to make recommendations on how to properly direct the supplemental budget passed in July towards helping our most vulnerable communities. On the federal level, the next coronavirus relief package known as the HEROES Act of 2020 is currently being negotiated in the Senate, which may implement free testing and treatment in BIPOC communities, improve racial data collection, and provide funding for health disparities research.

As fall semester is among us, it is essential to start gearing our policies to prioritize helping these more vulnerable populations in order to prevent the continuation of alarming death rates and exacerbating already existing inequalities.

Wei Li is a third-year Ph.D. student in the Chemistry and Chemical Biology program at Harvard University

Olivia Foster Rhoades is a fifth-year Ph.D. student in the Biological and Biomedical Sciences program at Harvard & is pursuing a concentration in STS at the Harvard Kennedy School. You can find her on Twitter as @OKFoster

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.